Artists that represented the cream of the crop. Songs emanating out of Philadelphia then resonating to all-points `round the globe. Music as soulfully sumptuous as it comes. Missives of messages as a unifying force. A logo that guaranteed “Grown Folks Music Only Here.” And a brand that stood for the past, present and future of African American class, pride and culture. These were and remain the hallmarks of Philadelphia International Records (PIR): more than a record company but a beacon representing Black Essence for all the universe to recognize.

“If Stax Records in Memphis represented the annals of Black Music at its roots core and Motown Records in Detroit represented what long-striving Black folks aspired to become, Philadelphia International Records staked its flag in Black people’s transcendental arrival.”

There within the fabled City of Brotherly Love [and, as Quiet Storm radio hostess “Ebony Moonbeams” (Dyana Williams) later amended, “and Sisterly Affection”], all the tenets of a new Black Renaissance coalesced into a most righteous seat at the welcome table.

Spearheaded in 1971 by prolific songwriting duo Kenneth Gamble & Leon Huff, PIR was the masterplan of men who had not only done their homework but also put their money where their mouths were in trials and errors. Huff met Gamble in 1964 when he came to take the place of a young Thom Bell in his group The Romeos. Kindred spirits in rhythm & business, Leon and Kenny forged their first of several endeavors together in 1966, Excel Records (sole single: “Gonna Be Strong” by The Intruders), swiftly renamed Gamble Records for which they picked up The Jaggerz, Dee Dee Sharp and The Butlers, led by a young Frankie Beverly, later to lead Maze. A brief partnership with Chicago’s legendary Chess Records in 1969 led to the duo launching Neptune Records for which they additionally snatched up The O’Jays, The Three Degrees, Billy Paul and Bunny Sigler who would become a greater presence as a songwriter/producer/arranger and in-house vocalist. However, a management shift at the top of Chess led to the shuttering of Neptune. Determined to never let this happen again, Gamble & Huff set their sights on higher ground.

Corporate giant CBS, home of Columbia and Epic Records, was looking to become a bigger player in Black Music to further expand its success with crossover superstars Sly & The Family Stone and smaller niche acts such as Buddy Miles, O.C. Smith, Ronnie Dyson and The Free Movement. Gamble & Huff fit the bill exquisitely with experience in what to do AND not to do, a treasure chest of faithful artists, gold card standard songwriting, and a rapidly developing army of producers, arrangers and musicians that would couch it all in trappings ranging from get down funk to penthouse plush. All they needed was strong national distribution, marketing, promotion and financial backing. The deal also included Mighty Three/Assorted Publishing, Gamble & Huff’s composing trust with old friend Thom Bell. As black ink was drying on white paper, so was one of the most incomparable musical meetings of the minds being birthed.

Excel, Gamble and Neptune all forged into Philadelphia International Records which kicked off its partnership with a slew of singles by new artists plus the album Going East by Soul-Jazz singer Billy Paul. The first PIR song to crack Billboard Magazine’s R&B Singles chart was the spring of `71 #10-peaker “You’re the Reason Why” by vocal quartet The Ebonys, a Leon Huff discovery out of Camden, New Jersey. Though the group scored one more Top 20 hit with “It’s Forever,” their other material fizzled. This marked a quick lesson for Gamble & Huff that would will out in the ensuing years.

Unlike Motown, PIR did not specialize in grooming talent. The artists they signed were generally very well-seasoned veterans either as recording artists and/or as performers who had weathered all the preparatory storms of “the road” or “chitlin circuit.” They’d paid plenty dues, learned their lessons and knew well to be appreciative of the opportunity to become part of a Black-owned operation funded by a major corporate entity that could take them places. This truth meant that PIR’s acts tended to be more mature, giving the company a strong adults-targeted base, though much of the music appealed to people of all ages. The early `70s were a powerful moment of change and upward mobility for many African Americans after the civil rights movement resulted in greater integrated opportunities for collegiate study, higher wage jobs and trades, suburban housing and entre’ into the middle class. More expendable income meant higher stakes in their free time for travel, romance, stylin’-n-profilin’, and the undeniable right to boogie down! While there were still many battles yet to wage with the Vietnam War raging overseas, President Nixon dippin’-and-dabblin’ on U.S., soil, and the infiltration of hardcore drugs into the inner city, Blacks were generally enjoying a higher quality of life. The artists and music of Philadelphia International Records provided the soundtrack for the highs and lows of all of this with some of the strongest R&B and Soul music of the era to waft from transistor AM radios to stereo FM stations and home audio systems.

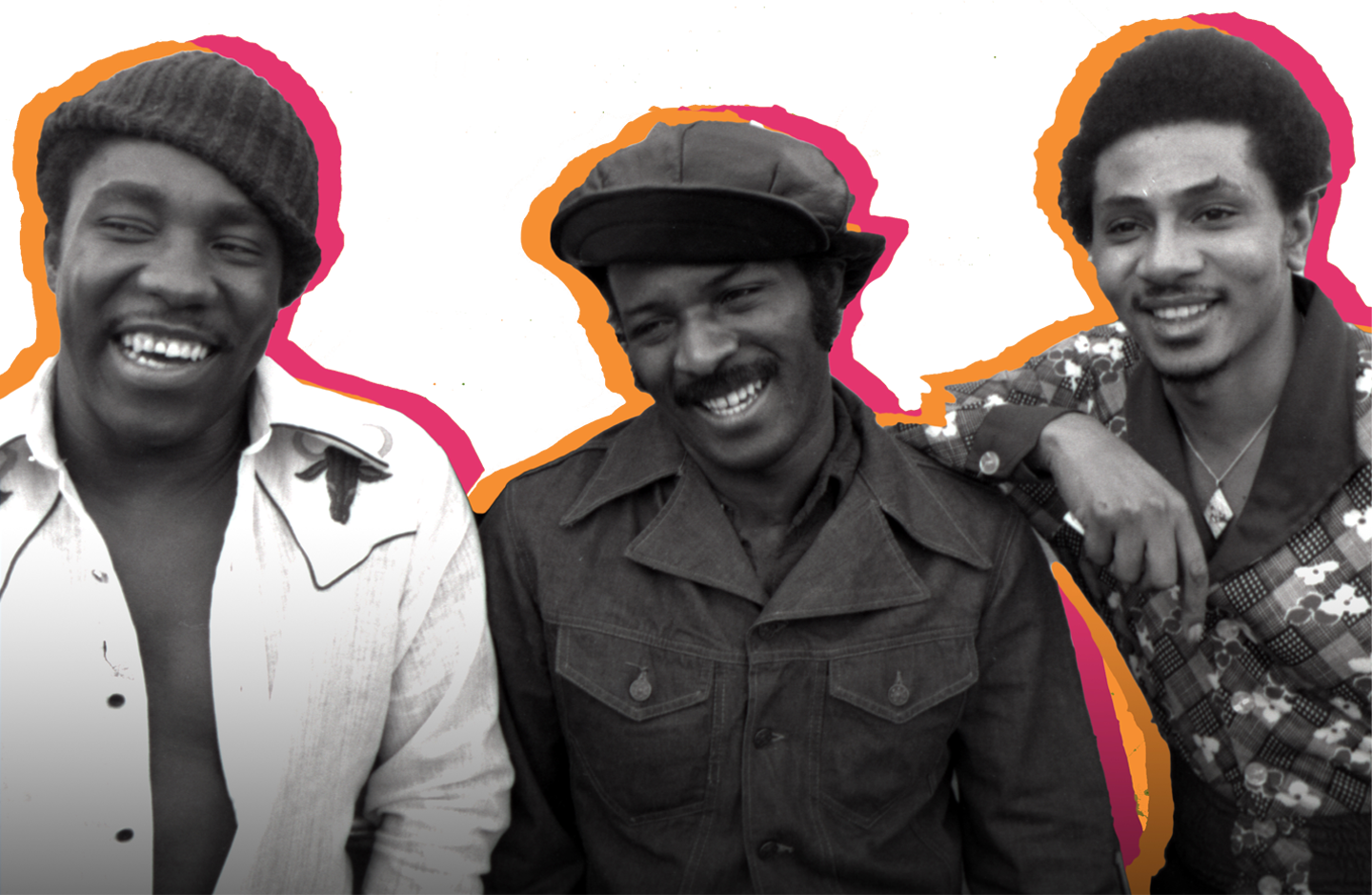

The first out-and-out smash for PIR arrived with the building blocks of a rumbling piano intro, a tight Latin groove topped with Jazz guitar ushering in majestic orchestration and six soulfully syncopated beats climaxing with the line, “WHAT THEY DOIN’!” The song was the summer of `72 sizzler “Back Stabbers” and the group was The O’Jays, down from a quintet to a trio and firing on all cylinders with the twin-engine leads of Walter Williams and Eddie Levert. This cautionary classic about two-timers of which to be wary picked up where The Undisputed Truth’s “Smiling Faces (Sometimes)” left off to become PIR’s first #1 single. By November, Philly locals Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes featuring a fiery lead singer named Theodore Pendergrass (fresh up from the drum throne) couldn’t have been more grateful that Thanksgiving to enjoy their first #1 hit with the sorrowful “If You Don’t Know Me By Now.” And ol’ jazz man Billy Paul didn’t know what to do with himself as he ascended overnight from supper club sensation to Soul’s most renowned cheater thanks to “Me and Mrs. Jones,” a Gold-seller that topped Billboard’s R&B chart for four weeks and was #1 Pop for three.

All of this music began to be known as “Philly Soul.” And though the form existed pre-PIR with related artists such as The Delfonics, The Stylistics and more, it truly began to flourish with what Gamble & Huff were achieving in house and what Thom Bell was accomplishing as an outside producer over on Atlantic Records with red-hot vocal quintet The Spinners waxing hits such as “I’ll Be Around,” “Could It Be I’m Falling in Love,” “Mighty Love” and many more. Additionally, some of PIR’s and Mighty Three’s most prolific writers and players were spreading the sound around to other locals such as Blue Magic.

However, it was within the PIR family that Philly Soul was flowing like water. The Blue Notes roared back with “The Love I Lost” (the drum beat by Earl Young becoming the proto Disco pulse of dancefloors worldwide), the tried and true Intruders hit back to back with the thoughtful and danceable “I’ll Always Love My Mama” and the mack daddy slow jam gemstone “I Wanna Know Your Name.” Meanwhile, female trio The Three Degrees broke through with the dreamy and wistful “When Will I See You Again” then added their vocal magic to a powerful instrumental that shined two-fold as the theme for Don Cornelius’ fast-rising Black Music television program “Soul Train” AND as the rousing anthem of their entire movement: The Grammy-winning “T.S.O.P. (The Sound of Philadelphia),” by MFSB (Mother Father Sister Brother), PIR’s incomparable house orchestra.

A woman’s place at PIR was on a throne - Queens of the Quiet Storm – ever classy, refined, tastefully sexy and wondrously talented vocally. After The Three Degrees came Jean Carn – fresh off of the highly respected indie Black Jazz label and profile-raising collaborations with Norman Connors to grace PIR with unforgettables such as “You Are All I Need,” “Don’t Let it Go to Your Head” and her career-best album, When I Find You Love. Gamble & Huff reached back for dynamic Dee Dee Sharp who gave them powerful readings of Terry Callier’s “What Color is Love,” 10-CC’s “I’m Not In Love,” “Invitation” and “I Love You Anyway.” Then up from the background came The Jones Girls, a trio of sisters Shirley, Brenda and Valorie who wrapped their ubiquitous talents around material ranging from the dancefloor classics “You Gonna Make Me Love Somebody Else,” “I Just Love the Man” and “Dance Tuned Into a Romance” to the richly evocative “At Peace with Woman,” “Who Can I Run To” (taken to #1 decades later by Xscape) and the spellbinding “Nights Over Egypt” (produced by Dexter Wansel with scholarly lyrics penned by the criminally unsung Cynthia Biggs). When The Jones Girls went on hiatus, Shirley stepped up and showed out with the chart-topping solo hit “Do You Get Enough Love.”

1976 marked the bicentennial of America’s independence which resounded heavily around Philadelphia, home of the Liberty Bell. Fittingly, it was also a triumphant year for Philadelphia International as Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes turned the nation’s eyes skyward with the anthem “Wake Up Everybody” practically a solo showcase for Teddy Pendergrass who already had big eyes for stardom on his own (seek out their performance of the song on “Soul Train” for evidence). Groomed for global love man supremacy, “Teddy Bear” began moisturizing undergarments with his self-titled solo debut followed by a string of platinum-plus sellers buoyed by steamy boudoir singles such as “Close the Door,” “Turn Off The Lights,”: “Come Go With Me,” “Only You,” “Love TKO” and “You’re My Latest, My Greatest Inspiration.” Teddy’s For Ladies Only concerts remain the sweet stuff of legend… Also in ’76, superstar siblings The Jacksons left Motown and their original moniker The Jackson 5 behind to arrive at PIR via a joint deal with Epic Records for two LPs that gave them more creative freedom and a more grown-up sound on gems such as “Show You the Way to Go,” “Good Times,” “Find Me a Girl” and the Platinum kick-off single, “Enjoy Yourself.”

Meanwhile, pioneering crossover great Lou Rawls turned his recording career completely around after a lackluster move from Capitol to MGM by joining PIR, debuting with the chart-topping cha-cha “You’ll Never Find Another Love Like Mine” followed by a string of seductive classics such as “Lady Love,” “See You When I Git There” and “Let Me Be Good To You.” Dexter Wansel, a dynamically musical individual who came to PIR as a member of the band Yellow Sunshine, rose from the writing/producing/arranging background to make a splash on the Jazz and R&B charts with the futuristic synthesizer groove “Life on Mars.” Disco dancefloors surged to the rock steady rhythm of the group People’s Choice’s Top 10 hit “Do it Any Way You Wanna” (on the TSOP subsidiary). And The O’Jays, who had been the most consistent hitmakers of the label – running the gamut from the singalong “Love Train,” the forceful “Give the People What They Want,” the tender “Darlin’, Darlin’ Baby (Sweet, Tender Love)” and the boudoir scorchers “Stairway to Heaven” and “Let Me Make Love To You” – gave PIR its last #1 of `76 with “Message in the Music,” which became the company slogan.

“Running across Philadelphia International’s hit streak of classic albums – projects minted to be listened to from first song to last, over and over – was a through-line of thought-provoking messages about all manner of life, love and survival.”

1976 marked the bicentennial of America’s independence which resounded heavily around Philadelphia, home of the Liberty Bell. Fittingly, it was also a triumphant year for Philadelphia International as Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes turned the nation’s eyes skyward with the On the back jackets or inner sleeves, Kenny Gamble (who Dexter Wansel immortalized on wax as “A Prophet Named K.G.”) often wrote short sermons that zoned in on themes within the album he felt were worthy of deeper comment. It could be about the importance of reconciliation in a relationship (The O’Jays’ “Cry Together”), respect down through the generations (The O’Jays’ “Family Reunion”), the continuance of life (Billy Paul’s sexy and controversial “Let’s Make a Baby”), the almighty dollar (“For The Love of Money”) or the dark history of Black people’s middle passage from Africa to America (“Ship Ahoy”). The sheer indomitable and rebounding BLACK-NUSS of it all was always right on the surface, never buried.

Black pride in art, back story and purpose was also evident to consumers before they even heard one note of music thanks to the eye-popping artwork helmed by Chinese master art director Ed Lee – be it stark paintings such as the gatefold for Billy Paul’s War of the Gods and The O’Jays Survival to the elegance of The Three Degrees self-titled debut LP or The Blue Notes’ To Be True or the graphic artistry of 360 Degrees of Billy Paul or MFSB’s eponymous debut LP (the cover depicting a heroin syringe in a funeral casket) – the imaging was as mind-blowing as the music inside. PIR wasn’t just about cranking out hits and superstars. It was about connecting and refracting Black culture for pan-global compassion and edification.

Once listeners placed the needle on the turntable, popped in a cassette or engaged their 8-track tape decks, the sound they heard was wraparound heaven, plunging them into sonic caverns of wonder thanks to the ears of engineer Joe Tarsia who made everything that emanated out of Sigma Sound Studios feel like a warm fresh laundered blanket. This was music hand crafted by Philly’s finest rhythm, horns, strings and vocal talents as arranged and orchestrated by geniuses such as Bobby Martin, Thom Bell, Vince Montana, Norman Harris, Jack Faith and John Usry.

As PIR continued to grow and flourish, the company stayed true to its penchant for rolling the dice with well-seasoned artists from The Dells out of Chicago to Archie Bell &The Drells out of Houston. They achieved one-off success with Philly’s own The Stylistics who hit big with “Hurry Up This Way Again” and even bigger with homegirl Patti LaBelle who sat at #1 for four weeks with “If Only You Knew.”

However, the artist Gamble & Huff and Philadelphia International Records were truly able to reinvent in the shining image she so deserved was the troubled Phyllis Hyman. Her reemergence in 1986 after three years away from recording with the breathtaking Living All Alone album then five years later with Prime of My Life (1991) gifted the planet with an enviable cache of classics, including “Old Friend” (the final composition of the great Linda Creed before she succumbed to cancer), “First Time Together,” “You Just Don’t Know,” “Meet Me on The Moon,” “When I Give My Love (This Time),” “When You Get Right Down To It,” “I Found Love” and a passionate cover of Bobby Caldwell’s “What You Won’t Do For Love.” The most bittersweet triumph was the song that FINALLY took the jazzy former Broadway ‘sophisticated lady’ all the way to the top of Billboard’s R&B chart on the wings of a new club groove made popular by the group Soul II Soul: the Nick Martinelli-produced “Don’t Wanna Change the World,” also PIR’s final R&B chart-topper. So perfect was Phyllis Hyman’s collaboration with PIR that even after her tragic suicide on June 30, 1995 (one week shy of her 46th birthday), she and PIR still had two full CDs worth of material “in the vault” to eventually console heartbroken fans.

“Not surprisingly, even when Gamble & Huff brought the curtain down on new music coming out of Philadelphia International Records in the early '90s, the richness of their sound continued to dominate the airwaves as sampled by a wide variety of creative crate-digging Hip Hop and Neo Soul artists and producers.”

Angie Stone lifted the coldblooded opening groove of “Back Stabbers” for “Wish I Didn’t Miss You.” French Montana folded in the orchestral intro of “Come Go With Me” for his galactic glide “Roll with Me.” Two majestic sections of MFSB’s “Something for Nothing” were utilized for Jay-Z’s “What More Can I Say.” The late, great Nipsey Hussle incorporated haunting vocal ambience from The O’Jays’ “Who Am I” for “All Get Right.” Big Pun jumped on the hook and the groove of “Darlin’, Darlin’ Baby” for his sex-drenched “I’m Not a Playa.” Ciara sang an interpolation of The Blue Notes’ “If You Don’t Know Me By Now” for “Never Ever” while Usher usurped the bassline from their “Is There a Place for Me” for “Take Your Hand.” Mariah Carey used punctuation from The O’Jays’ “Let Me Make Love to You” for “Make it Look Good.” And Atlanta duo OutKast (working with production team Organized Noize) decelerated the groove of their song “GhettoMusick” with a headily reworked hook from Patti LaBelle’s “Love, Need and Want You.” These are but a handful of scores of PIR music refashioned to create new hits for younger generations.

2021 will mark the 50th anniversary of Philadelphia International’s entrance into the world of music to kindle hearts, lift spirits, sharpen minds, warm loins and unite people around the world on ‘love trains’ and ‘soul trains’ showing no signs of running out of gas anytime soon. Though many of its finest contributors in the spotlight and behind the scenes have ascended into the hereafter…and the very buildings that housed their offices and studios are no longer in their possession, the spirit of PIR presses on! In the words of Gene McFadden & John Whitehead, songwriters who earned their rightful 15 minutes of fame circa `79 as hitmakers McFadden & Whitehead, when it comes to all things Philadelphia International Records: “Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now.” It’s…forever.

October 5, 2020